2020 - The year of Restorations

Now that we seem to be on the other end of the pandemic, I wanted to take a moment to look back on some of the projects that kept me busy. Restorations were the name of game during covid times. With productions shut down and uncertainty in the theatrical marketplace, I had time in my schedule to breathe new life into some of my favorite classics.

Over the last year, I have restored;

Let’s take a look at a couple of these titles and talk about what it means to remaster a film with our contemporary toolset.

The Process

The process for remastering classic titles is very similar to finishing new theatrical work with a couple of additional steps. The first step is to identify and evaluate the best elements to use. That decision is easy for digitally acquired shows from the early 2000’s. In those instances, the original camera files are all that exist and are obviously the best source. Film shows are where it gets particularly ambiguous. There is a debate whether starting from the IP or original negative yields better results. Do we use the original opticals or recreate them from the elements? Black and white seps vs faded camera neg? These questions all need to be answered before you begin the work. Usually I prefer to start with the OCN when available.

Director Scanner

Arri Scan

Scanning

Scanning is arguably the most critical part of the process. Quality and success will live or die by the execution of great scans. Image breathing, movement, and general sharpness are issues to look for when evaluating. Scans should not be pretty but rather represent a digital copy of the negative. In a perfect closed-loop system, a scanned piece of film, once shot back out on a calibrated recorder needs to closely match the original negative.

Digital Restoration

The next step in making an old project shiny and new is to repair any damage to the film from aging or that was inherent in production. this includes painting out splice lines, gate hairs, dirt, and scratches. Film processing issues like breathing or turbulence can also be taken care of in this step. I prefer to postpone flicker removal until the grading step since the contrast will have an effect on the amount of flicker to remove. Some common tools used for restoration include MTI and PF Clean. This work is often outsourced because of the high number of man-hours and labor costs associated with cleaning every frame of film. Some companies that do exceptional restoration work are PrimeFocus and Prasad among others.

Grading

Grading restoration titles is a total sub-discipline from grading as a whole. New theatrical grading starts with references and look development to achieve a certain tone for the film. There is a ton of work that goes into this process. Restoration grading differs since the goal is staying true to that original intent. Not reimagining it. Much like new theatrical grading, a good reference will set you up for success. My preferred reference is a filmmaker-approved answer print. These were the master prints that best represented the filmmakers’ creative intent.

A good practice is to screen the print and immediately set looks for the scans getting as close as possible at 14fl projected. An upgrade to this workflow is to use a projector in the grading suite like a Kinoton. These projectors have remote control and cooling. This allows you to rock and roll the film. You can even freeze-frame and thanks to the built in cooling your film doesn’t burn. Setting up a side-by-side with the film vs digital is the best way to ensure you have a match to the original intent. These corrections need to happen using a good color management system. Aces for example has ODTs for theatrical 48nits which is the equivalent of 14fl. Once you have a match to the original, the enhancement can start.

There would be no point in remastering if it was going to look exactly like the existing master. One great reason to remaster is to take advantage of new advancements in HDR and wide color gamut formats. Film was the original HDR format containing 12 stops of range. The print was the limiting factor, only being able to display 8 of those stops. By switching the ODT to PQ P3D65, we can take advantage of the larger container and let the film display all that it has to offer.

My approach is to let the film land where it was originally shot but tone-mapped for PQ display. This will give you a master that had the original intent of the print but in HDR. I often use an LMT that limits the gamut to that of the emulsion used for original photography. This also ensures that I’m staying true to the film's original pallet. Typically there is some highlight balancing to do since what was white and “clipped” is now visible. Next is to identify and correct any areas where the contrast ratios have been disrupted by the increased dynamic range. For example, if there was a strongly silhouetted shot, the value of the HDR highlight can cause your eye to iris down changing the perception of the deep shadows. In this case, I would roll off the highlights or lift the shadows so the ratio stays consistent with the original. The extra contrast HDR affords is often welcomed but it can cause some unwanted issues too. Grain appearance is another one of those examples.

Grain Management

Film grain is one of those magic ingredients. Just like salt, you miss it when it is not there and too much ruins the dish. Grain needs to be felt but never noticed. It is common for the noise floor to increase once you have stretched the film scan to HDR ranges. Also, the grain in the highlights not previously visible starts to be seen. To mitigate this, a grain management pass needs to be implemented. This can come before the grade, but I like to do this after since any contrast I add will have an effect on the perceived amount of noise. Grain can impart a color cast to your image, especially if there is a very noisy blue channel. Once removed this needs to be compensated for and is a downside of working post grade. It is during this pass that I will also take care of flicker and breathing which the grade also affects. My go-to tool for this is Neat Video. You would think that after a decade of dominance some software company would have knocked Neat off their throne as king of the denoise, but it hasn’t happened yet. I prebake the scans with a Neat pass (since Baselight X doesn’t play nicely with Neat yet.) Next, I stack the Neat’ed scan and the original as layers. This allows me to blend in the amount of grain to taste. The goal of this pass is to keep the grain consistent from shot to shot, regardless of the grade. The other, and most important goal is to make the grain look as it did on the print.

Dolby Trim

After the HDR10 grade is complete, it’s time for the Dolby trim. I use the original 14 FL print match version as a reference for where I want the Dolby trim to clip and crush. Once all the trims have been set, I export out a Dolby XML expecting rec2020 primaries as input. Yes, we graded in P3, but that gamut will be placed into a 2020 container once we export.

Mastering

Once all the work has been completed it’s time to master. Remasters receive the same treatment as new theatrical tiles when it comes to deliverables. The common ones are as follows:

Graded PQ P3D65 1000nit 16bit Tiff Files or ACES AP0 EXRs

Un-Graded PQ P3D65 16bit Tiff files or ACES AP0 EXRs

Graded 2.6 XYZ DCDM 14fl

Graded PQ XYZ 108nit 16bit Tiff Files or ACES AP0 EXRs for Dolby Vision Theatrical

Bt1886 QT or DPX files created from a Dolby XMLIMF PQ rec2020 limited to P3D65 1000nit

Case Studies

Perfect worlds do exist but we don’t live in one. Every job is a snowflake with its own unique hurdles. Remastering tests a colorists abilities across many disciplines of the job. Stong skills in composting, paint, film manipulation, and general grading is what is required to achieve and maintain the original artistic intent. Here are two films completed recently and a bit on the challenges faced in each.

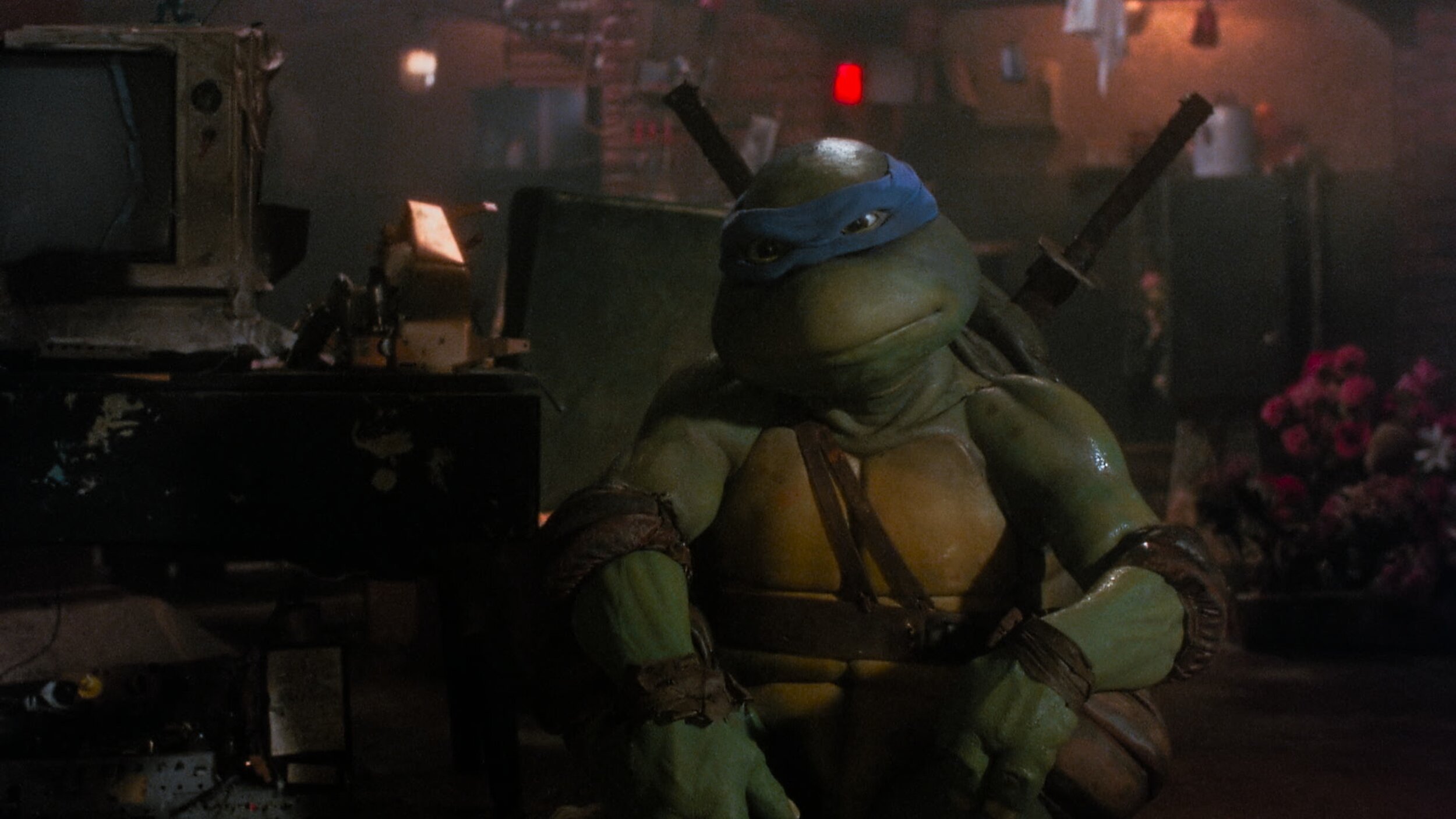

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles

For those of you that don’t know the Ninja Turtles are near and dear to me. Not only was I a child of the 80s, but my Father was in charge of the postproduction on the original cartoons. He also wrote and directed many of them. When this came up for a remaster, I jumped at the chance to get back to my roots.

This film only required an SDR remaster. The output delivery was to be P3 D65 2.6 gamma. I set up the job using Baselight’s color management and worked in T-Log E_Gamut. The DRS was performed by Prasad with additional work by yours truly BECAUSE IT HAD TO BE PERFECT!

There were two main color hurdles to jump through. First, some scenes were very dark. I used Baseligt’s boost shadow tool to “dig” out detail from the toe of the curve. This was very successful in many of the night scenes that the film takes place in.

Another trick I used was on the Turtle’s skin. You may or may not know, but all the turtles have different skin colors. Also, most folks think they are green, when in fact there is very little green in their skin. They are more of an olive. To make sure the ratio of green to yellow was correct I converted to LAB and graded their skin in that color space. Once happy, I converted it back to T-Log E-Gamut. LAB is a very useful space for affecting yellow tones. In this space, I was able to tweak their skin and nothing else. Sort of like a key and a hue shift all in one.

The SDR ended up looking so good that the HDR was finished too. The HDR was quick and painless because of Baselight’s built-in color management. Most of the heavy lifting was already done and only a few tweaks needed.

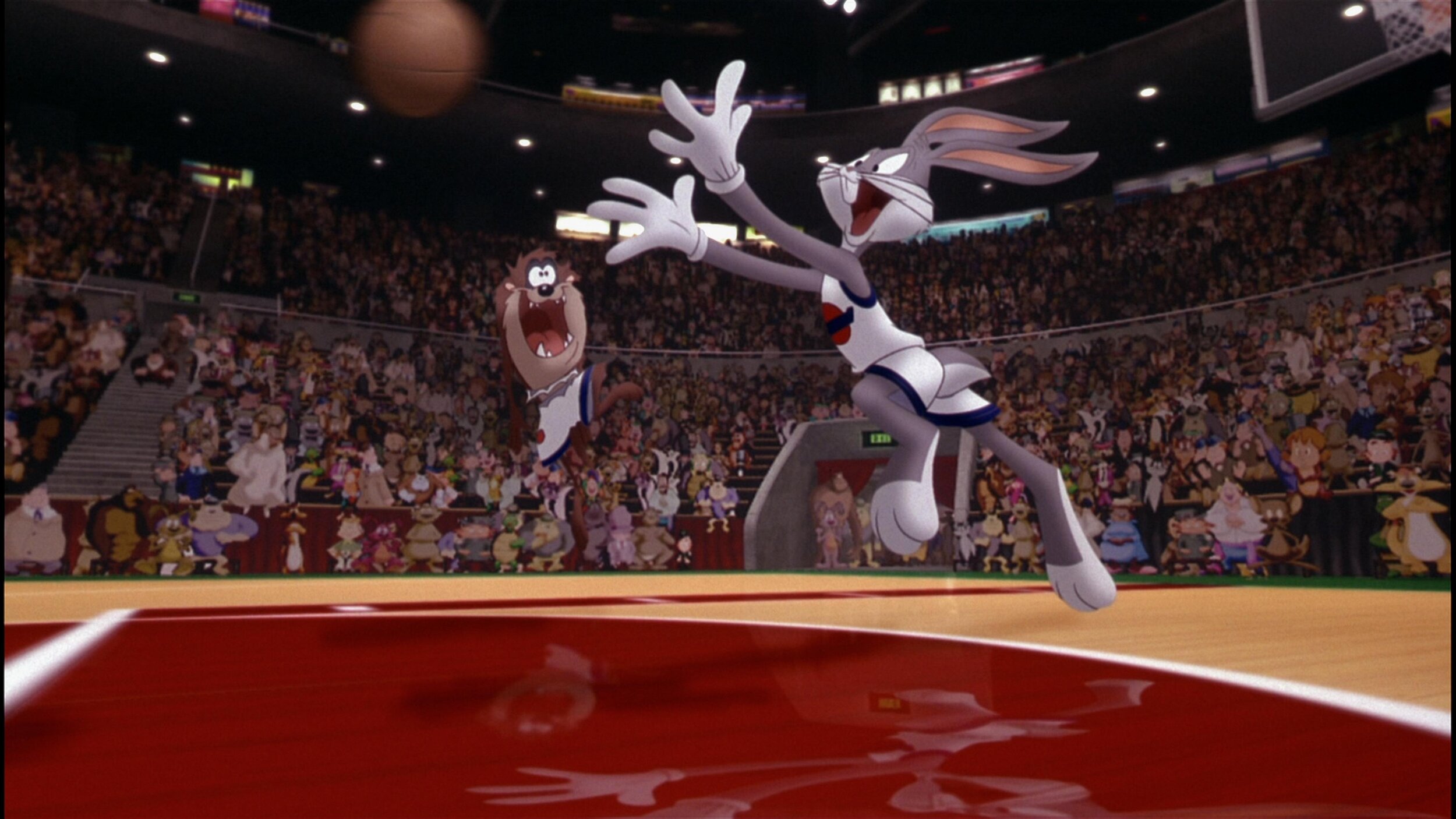

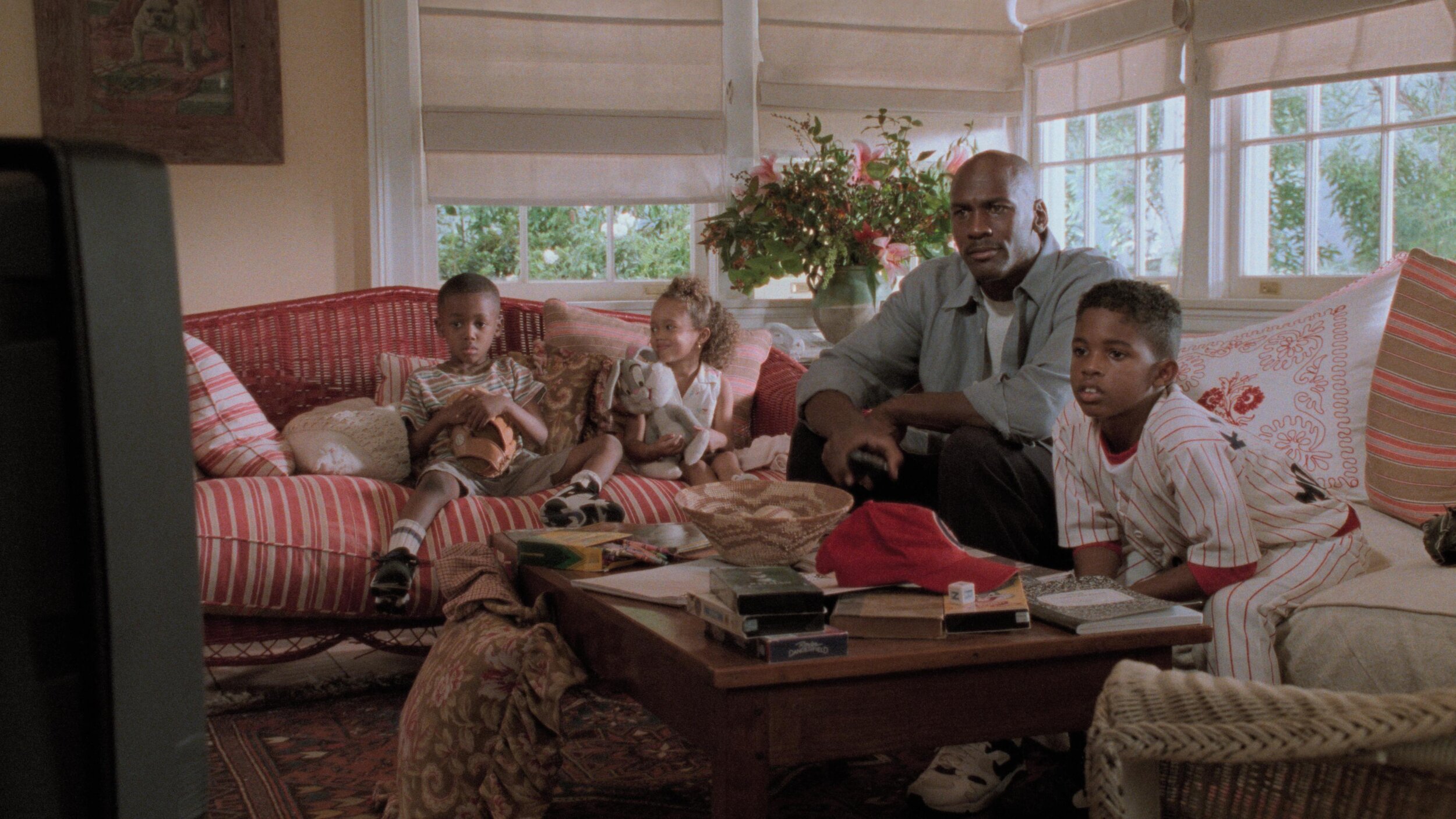

Space Jam

Space Jam was a formative film from my youth. Not only did I have Jordan’s at the time, but I was also becoming a fledgling animation nerd (thanks Dad) when this film was released.

I set up the project for ACES color management with a Kodak LMT that I had used for other films previously. This reigned in the extreme edge of gamut colors utilized in the animation.

The biggest challenge on this project was cleaning up some of the inherent artifacts from 1990’s film recording technology. Cinesite performed all of the original composites, but at the time they were limited to 1k film recording. To mitigate that in a 4k world, I used Baselight’s texture equalizer and convolutional sharpen to give a bit of snap back to the filmed out sections.

Vishal Chathle supervised the restoration for the studio. Vishal and I boosted the looney tunes to have more color and take advantage of the wider gamut. The standard film shots, of which there were few, were pretty straightforward. Corrected mostly with Baselight’s Basegrade. Basegrade is a fantastic tool where the corrections are performed in linear gamma. This yields a consistent result no matter what your working space is.

Joe Pytka came in to approve the grade. This was very cool for me since not only did I grow up watching this film of his, but also all those iconic Superbowl commercials from the 90’s that he did. A true master of camera. He approved the grade but wished there was something more we could do with the main title. The main title sequence was built using many video effects. To recreate it would have cost a fortune. We had the original film out of it, but it looked pretty low res. What I did to remedy this was to run it through an AI up-rezer that I coded a while ago for large format shows.

The results were astounding. The titles regained some of their crisp edges that I can only presume were lost from the multiple generations of opticals that the sequence went through. The AI was also able to fix the aliasing inherent in the low res original. In the end, I was very proud of the result.

The last step was grain management. This show needed special attention because the grain from the Jordan plate was often different from the grain embedded in the animation plate that he was comped into. In order to make it consistent. I ran two de-grain passes on the scan. The first took care of the general grain from the original neg. The second pass was tuned to clean up Jordan’s grain that had the extra layer of optical grain over the top. It was a complicated noise pattern to take care of. Next, I took the two de-grained plates, roto’ed out Jordan, and re-comp-ed him over the cleaned-up plate. This gave consistency to the comps that were not there in the original.

Another area where we helped the comps were in animation error fixing. Some shots had layers that would disappear for a couple of frames, or because it was hand-drawn, a highlight that would disappear and then reappear. I used Baselight’s built-in paint tool to repair the original animation. One great feature of the paint tool is its ability to paint on two’s. An old animation trick is to only animate at 12fps if there isn’t a lot of motion. Then you shoot each frame twice. This halves the number of frames that need to be drawn. When I was fixing animation issues I would make a paint stroke on the frame and Baselight would automatically hold it for the next one. This cut down my work by half just like the original animators!

I was honored to help restore this piece of animation history. A big thanks to Michael Borquez and Chris Gillaspie for the flawless scanning and deep investigation of the best elements to use. Also a tip of the cap to Vishal Chathle for all the hard work and lending me his eagle eye!

Final Thoughts

Restoration Colorist should be a credit on its own. It’s unfortunate that this work rarely gets recognized and even less frequently gets credit. It is hard enough to deliver a director’s artistic vision from scratch. It’s arguably even harder to stay true to it 30 years later. Thanks for reading and check out these projects on HBO Max soon!