Hopefully, this helps my fellow hue benders out there. Let me know if you disagree with anything in the comments. I always appreciate new ways of looking at things.

John Daro, Senior Colourist, Warner Bros

John Daro is a Lead Digital Intermediate (DI) colourist at Warner Post Production Creative Services, a division of Warner Media. He has supervised the finishing and grading of many feature films, television pilots, commercials, and music videos for clients, including all the major studios, in addition to independent productions.

Daro started his career at the film lab FotoKem. His first notable achievement was architecting a direct-to-disk dailies pipeline. From that role, he moved on to film scanning-recording and, with the DI process's creation, his current position as a finishing colourist. His past jobs gave him a mastery over colour transforms, and he started to couple those strengths with the art of cinematography. He continued to pioneer post-production techniques, including 3D conversion and the early days of HDR imaging. As a founding team member of their digital film services department, he helped FotoKem achieve its status as one of the premier post houses in the film and television post-production industry.

In this interview, Daro talks to us about how colour can be used to shape an audience’s interpretation of a film and provides examples of how he’s used colour to help communicate a narrative in the past.

How do you think colour shapes the way audiences perceive film?

It's funny that you asked how colour shapes the audience's perception because, in a way, the colour process is literally “shaping” what we want you to see and what we don't. At its most basic, colour finishing is the process of highlighting and subduing certain key areas which directs the viewer’s attention to where the filmmakers intended. Before digital colour grading, cinematographers highlighted these key areas through shadow, light, depth of field and lens effects. Photochemical timing changes were limited to colour and density. Nowadays, the sky's the limit with shapes, articulate roto masks and matte channels. Ultimately, the end goal of all these tools is to make it feel natural and true to the story and highlight key moments necessary for the viewer to absorb the supporting narrative. It's an old cliche, but a picture tells a thousand words.

How have you used colour to communicate with an audience?

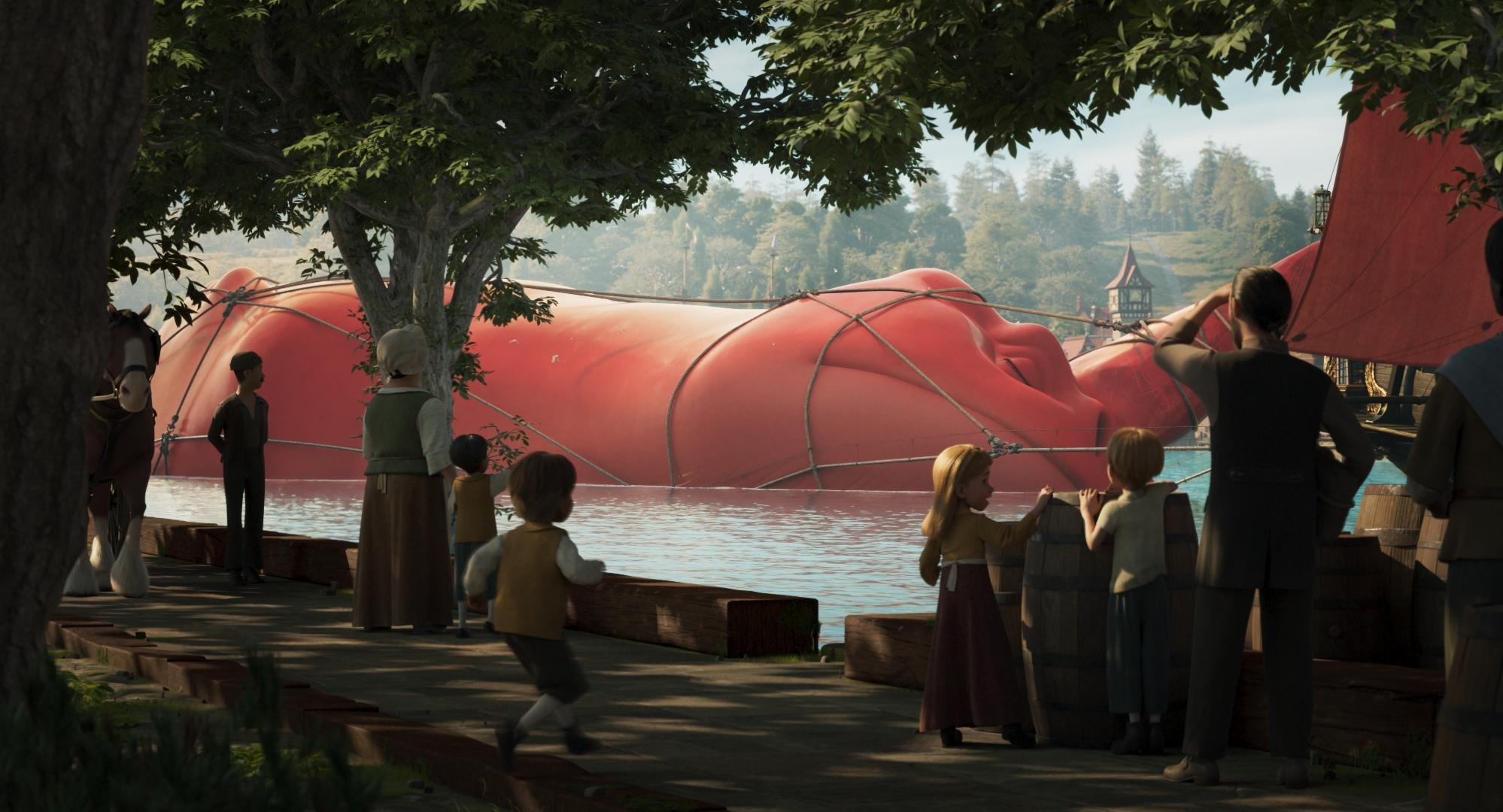

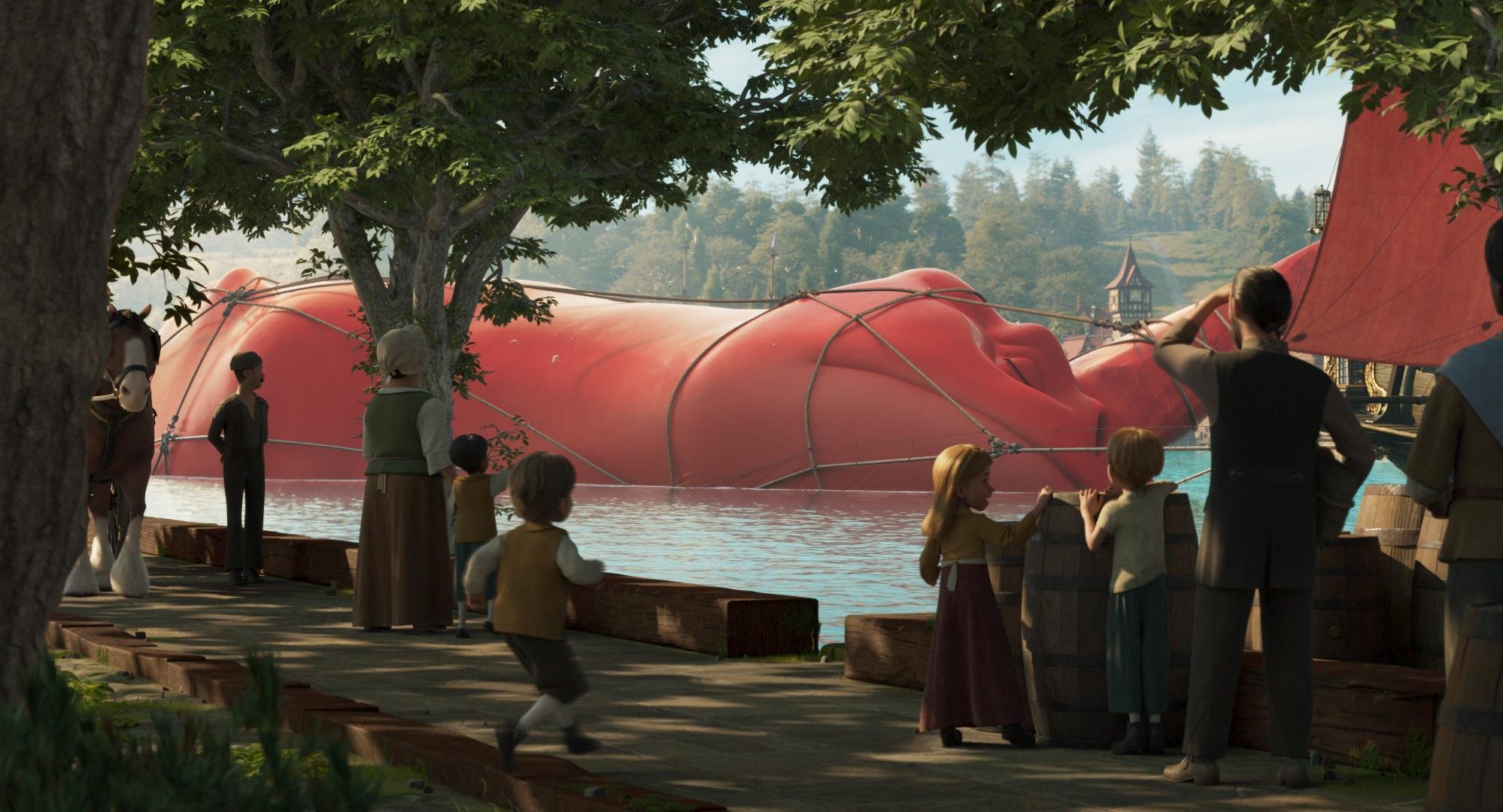

A couple of examples that popped into my mind involve using dynamics to simulate coming out of a bright area. I think I used this technique most effectively in Laika’s The Boxtrolls. When Eggs, the film’s protagonist, came out of the sewer for the first time, we applied a dynamic luminance adjustment to simulate what your eyes would do when adjusting to a bright light coming from the darkness.

Another example is Steven Soderbergh's Contagion, where colour choices define geographical location to help the viewer know where they were without needing additional information. I also used this technique in Natalie Portman’s adaptation of Amos Oz’s A Tale of Love and Darkness. For this film, we were dipping through memories and a fantasy world. Colour choices defined the real world versus the world inside the character’s head.

Can you talk us through your involvement in choosing and implementing a colour palette for a specific scene/film?

So many of these decisions are decided upfront through lighting, production design and wardrobe. It's always a pleasure to be brought in on a project early enough to have been part of those conversations and understand the motivation behind the choices. I feel there's great value for everybody to be on the same page and know how specific colours on the set will render in the final output.

Look development can have many muses. A style guide, concept art and a reference deck are great tools. I like to start by picking two or three key colours that are important to the story, symbolize a character, or represent a message. Then the objective is to find the best way to shift and enhance to make a split complementary palette. Contrast and simplicity are at the heart of the finest design in my opinion.

Do you think colour is the backbone of emotion in film?

I don't think so, no. I think sound is. Smell would be even more evocative, but luckily for the Jackass movies, smell-o-vision didn't catch on!

I prefer to grade with the latest mix. It's the sum of all the parts that make a great cinematic symphony. Colour and sound must be playing in concert, similar in tone or in contrast but always together.

I think that kind of sensory feeling might be ingrained in our DNA. Whenever I hear the opening to Peter and the Wolf, I visualize spring greens. It doesn't work the other way, however. I don't hear Peter and the Wolf every time I see green. Colour must be taken in context. Green can make you feel safe and calm like a lush field of grass blowing in the wind does. At the same time, it can evoke feelings of jealousy or sickness. It all depends on context and the motivation behind the story being told.

How do you know when a specific colour scheme does or doesn’t work?

There are a few academic reasons I could give you. For example, certain colours clash with other colours. Certain colour harmonies are not particularly pretty, but that doesn't mean that you can't use those mismatches. Especially if what you're going for is to make the viewer uncomfortable or uneasy. Colour is subjective; balance is not.

Ultimately, the real answer is feeling it in your gut. You know when it’s right. I have an internal rule when taking my passes. The reel is done when I can watch it down and have less than three tweaks to make. You are never really finished. Most often, you just run out of time.

How do you work with the director and cinematographer to achieve a specific look in a film?

I first watch a rough cut or read the script and get an idea of the story. Next, I take camera tests and start to build a basic look. The goal with this V1 transform is to find something that works for the cinematographer and gets them repeated results in different lighting conditions. Obviously, it should also have an aesthetically pleasing visual component. It's important when building a look to ensure that the camera still behaves as expected regarding sensitivity and dynamic range. You don’t want to bake anything that could hamper the original photography. Essentially, make sure mid-grey still maps to mid-grey.

Once we have dailies, the process begins again, where I might have a V2, V3, or V4 version of the look that we're going for. I put those in a still gallery on a server for remote viewing, and we constantly update the conversation forum page with feedback from the creatives. I maintain before and afters of all versions to ensure we improve and never go backwards creatively. The last step is to ensure that the look works for the story once the film is assembled. Tweaks are made to the show look and certain scenes get special treatments for effect.

CDLs are a vital part of this process as well. Grading your dailies is very important for ensuring that there are no surprises when everyone gets to the DI theatre. I've had past experiences where producers see something that has the final grade, but it's too far of a departure from what the look was in editorial. To combat this reaction, we always want to ensure that the look is consistently maintained from the first shot out of the camera through to the final finish.

How can colour set the tone for a scene?

To set the tone, it's all about warmer, colder, brighter, or darker. As I've already touched on, it's really important to pick a few colours that you want to enhance and then let the background support that enhancement, whether through a complimentary value or making it recede. They're also the obvious washes that you can do. For example, if you make a scene very red, the warmth invokes a sense of romance or love. It can also yield a literal hot vibe. Something very cold, very desaturated invokes a sense of bleakness or a dystopian feeling. Magenta's a weird one because it can be warm and cold at the same time. Depends on the context and how it's used. Green-yellow also functions similarly. It can seem sickly and off, but it can also be romantic and warm, depending on what side of the hue you're on. I don't know where these generalities came from, but they're almost universal at this point. My gut is that human evolution has something to do with it. I think the responses to these colours helped us survive at some point. When I say it’s in our DNA, I do mean just that.

What technical difficulties do you come across with undertaking this critical part of film production?

You can avoid many technical difficulties by ensuring you’re doing no harm to your pixels. The most important thing is that you have a colour-managed pipeline, in that you’re never working on what the film looks like, but rather what the film was captured as. Make sure you’re always working in a photon real-world scene-referred way. At that point, the displays don’t matter as much. They simply target what you’re trying to hit. They can always be adjusted after the fact if there are technical concerns. I always work with soft display-referred transforms that gradually roll off your highs and also have a nice toe in the black. This generally helps cut down on the number of technical issues.

Past that, it's all about keeping your eye on the scopes and ensuring there are no technical glitches in the actual capture or renders like quantization, dead pixels, hits or bad frames. All it takes is an eye for detail and a great QC department.

How does your role as colourist differ when working on animation compared with live action films?

At the core, the two are very similar. The same principles that make a strong image still hold true regardless of how the image was created. Modern render engines are very good at doing what light does. So much so that a lot of DoP buddies of mine are pre-vising lighting setups virtually.

Nowadays, that line is being blurred even further, where some films can be comprised of mostly VFX shots. Many of these setups, especially with the advent of digi doubles, are not very different from a fully animated picture.

Now, if we’re defining a “live-action” shot as being something captured with a camera, and no further manipulation, then the biggest difference comes from the workflow. For example, if you take a live-action setup that has been shot with clouds and maybe some inconsistent lighting situations, your first step is technical colour correction just to balance the shots together. You don't have this problem with animation, but you do have a similar situation where you might have many artists working on the same scene. This can sometimes lead to slight inconsistencies that must be smoothed out.

A huge advantage of CG-originated shots is that they tend to have advanced matte channels. These could be as simple as a matte for the main character or as complicated as depth or normals. These additional tools allow for more complex grades but also increase the time that you spend on each shot.

Can you tell us about your grading suite? What could you not be without while at work?

My grading suite looks like a hot mess. Imagine the Great Wall of monitors. I have two x300s, and two GUI monitors for Baselight, one extra wide LG for what I call my Swiss Army box and an admin computer. The most important display is my Christie 4k projector. I also have an LG C2 to simulate a consumer experience.

The most important machine in my tool set is the Swiss Army box. Essentially, it's a super micro chassis with four a6000s that has every single piece of post-production software that has ever been useful. I also use this box for coding and the development of my own in-house tools. I would consider this machine mission-critical. Second to that, the next most important piece of gear would be an external scope. Your eyes can lie to you, but scopes never do. Software scopes have made huge advancements in recent years. I can't say I use the external one every day, but when you need one, there really isn't a substitute.

How does Baselight aid your role as a colourist?

There's a lot of great software out there and I always say use the right tool for the right job. For most of my jobs, that ends up being Baselight. The reasons are straightforward. Firstly, the colour science in the machine is second to none. Next, I appreciate the simplicity of the interface. When colouring long form, most of what you're doing is manipulating groups of many shots. Baselight makes this very easy to do. The other thing I can't live without is how Baselight organises and categorises. When you get towards the end of the project, things get hectic, and it's very nice to be able to sort and view in any way that a project demands. Often this has to do with missing visual effects or work I need to get to after the session. I use categories and marks so that I always know what the status of a scene is at any given time. This organisation also aids in communication. I can always keep post supervisors up to date with reports. Additionally, my in-house team always knows what needs to be done and what is already completed based on the organisation that we have put in place. I've always felt that Baselight was built by people who do the job of colour – not by committees or nonpracticing theoreticians.

What are you working on now/next?

I’m currently finishing a docuseries directed by Allen Hughes for FX about Tupac Shakur’s life and relationship with his mother called Dear Mama. The interviews have an exciting cognac look that I can’t wait to share. The first part premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and was very well received.

Later this month, I will be finishing a feature called Sweetwater. It’s about the story of the first black NBA player, Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton. It is a period piece, so a lot of fun in the colour department. We contemplated a black-and-white double X look for the show but ultimately landed on a derivative of an Ektachrome simulation that I had built a while ago. It has a super cool look if I do say so myself.

We are also supporting pre-production and dailies on A Gun on Second Street. This show is shooting on film, which is always pleasurable and exciting. The look for the show is a straightforward Kodak film vibe, expertly lensed by Leo Hinstin.

While we are on the topic of film shows, I’m also supervising the remastering of Superman II (yes, both cuts.) This will be released in early 2023 just in time to get people excited about Michael Shannon’s General Zod in The Flash. Kneel before Zod!

Additionally, my team and I will return to animation early next year for an upcoming Netflix feature. More on that later at www.johndaro.com.